A Chinese threat actor has developed new capabilities to target air-gapped systems in an attempt to exfiltrate sensitive data for espionage, according to a newly published research by Kaspersky yesterday.

The APT, known as Cycldek, Goblin Panda, or Conimes, employs an extensive toolset for lateral movement and information stealing in victim networks, including previously unreported custom tools, tactics, and procedures in attacks against government agencies in Vietnam, Thailand, and Laos.

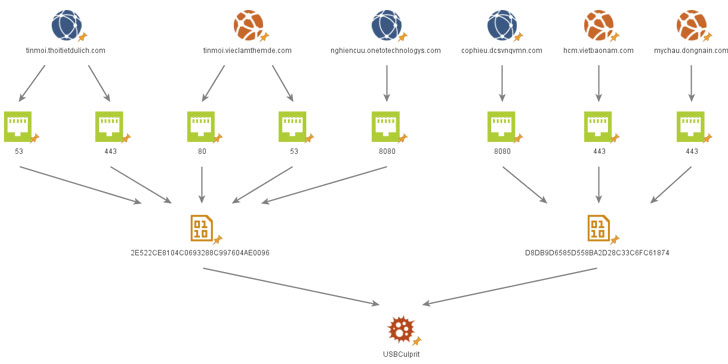

“One of the newly revealed tools is named USBCulprit and has been found to rely on USB media in order to exfiltrate victim data,” Kaspersky said. “This may suggest Cycldek is trying to reach air-gapped networks in victim environments or relies on physical presence for the same purpose.”

First observed by CrowdStrike in 2013, Cycldek has a long history of singling out defense, energy, and government sectors in Southeast Asia, particularly Vietnam, using decoy documents that exploit known vulnerabilities (e.g., CVE-2012-0158, CVE-2017-11882, CVE-2018-0802) in Microsoft Office to drop a malware called NewCore RAT.

Exfiltrating Data to Removable Drives

Kaspersky’s analysis of NewCore revealed two different variants (named BlueCore and RedCore) centered around two clusters of activity, with similarities in both code and infrastructure, but also contain features that are exclusive to RedCore — namely a keylogger and an RDP logger that captures details about users connected to a system via RDP.

“Each cluster of activity had a different geographical focus,” the researchers said. “The operators behind the BlueCore cluster invested most of their efforts on Vietnamese targets with several outliers in Laos and Thailand, while the operators of the RedCore cluster started out with a focus on Vietnam and diverted to Laos by the end of 2018.”

Both BlueCore and RedCore implants, in turn, downloaded a variety of additional tools to facilitate lateral movement (HDoor) and extract information (JsonCookies and ChromePass) from compromised systems.

Chief among them is a malware called USBCulprit that’s capable of scanning a number of paths, collecting documents with specific extensions (*.pdf;*.doc;*.wps;*docx;*ppt;*.xls;*.xlsx;*.pptx;*.rtf), and exporting them to a connected USB drive.

What’s more, the malware is programmed to copy itself selectively to certain removable drives so it can move laterally to other air-gapped systems each time an infected USB drive is inserted into another machine.

A telemetry analysis by Kaspersky found that the first instance of the binary dates all the way back to 2014, with the latest samples recorded at the end of last year.

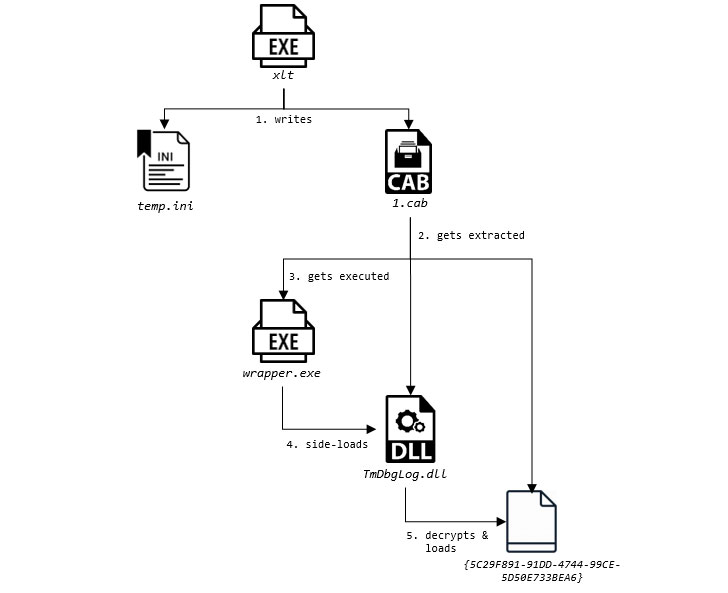

The initial infection mechanism relies on leveraging malicious binaries that mimic legitimate antivirus components to load USBCulprit in what’s called DLL search order hijacking before it proceeds to collect the relevant information, save it in the form of an encrypted RAR archive, and exfiltrate the data to a connected removable device.

“The characteristics of the malware can give rise to several assumptions about its purpose and use cases, one of which is to reach and obtain data from air-gapped machines,” the researchers said. “This would explain the lack of any network communication in the malware and the use of only removable media as a means of transferring inbound and outbound data.”

Ultimately, the similarities and differences between the two pieces of malware are indicative of the fact that the actors behind the clusters are sharing code and infrastructure, while operating as two different offshoots under a single larger entity.

“Cycldek is an example of an actor that has broader capability than publicly perceived,” Kaspersky concluded. “While most known descriptions of its activity give the impression of a marginal group with sub-par capabilities, the range of tools and timespan of operations show that the group has an extensive foothold inside the networks of high-profile targets in Southeast Asia.”

0 Commentaires