In mid-April, our threat monitoring systems detected malicious files being distributed under the name “on the new initiative of the World Bank in connection with the coronavirus pandemic” (in Russian) with the extension EXE or RAR. Inside the files was the well-known Rovnix bootkit. There is nothing new about cybercriminals exploiting the coronavirus topic; the novelty is that Rovnix has been updated with a UAC bypass tool and is being used to deliver a loader that is unusual for it. Without further ado, let’s proceed to an analysis of the malware according to the rules of dramatic structure.

Exposition: enter SFX archive

The file “on the new initiative of the World Bank in connection with the coronavirus pandemic.exe” is a self-extracting archive that dishes up easymule.exe and 1211.doc.

SFX script

The document does indeed contain information about a new initiative of the World Bank, and real individuals related to the organization are cited as the authors in the metadata.

Contents of 1211.doc

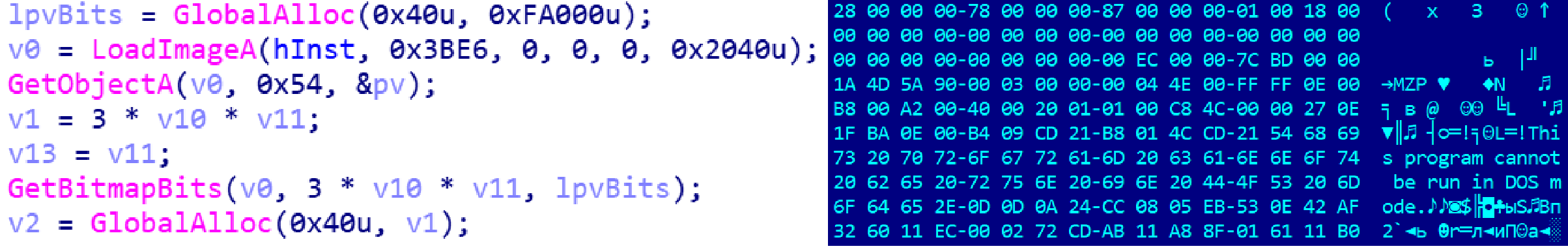

As for easymule.exe, its resources contain a bitmap image that is actually an executable file, which it unpacks and loads into memory.

Loading the “image”

Hook: enter UAC bypass

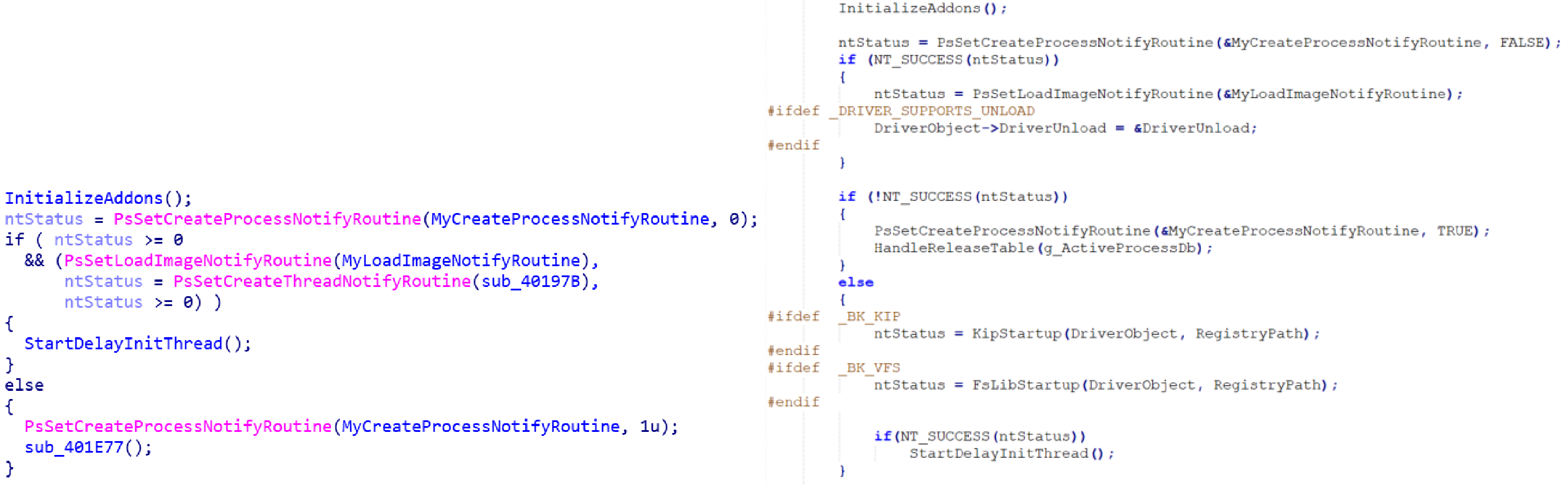

The code of the PE loaded into memory contains many sections remarkably similar to the known Rovnix bootkit and its modules, the source code of which leaked back in 2013.

Left: source of the malware; right: leaked Rovnix source code (bksetup.c)

However, the file under analysis reveals innovations clearly added by authors, based on the original Rovnix source code. One of them is a UAC bypass mechanism that uses the “mocking trusted directory” technique.

With the aid of the Windows API, the malware creates the directory C:Windows System32 (with the space after Windows). It then copies there a legitimate signed executable file from C:WindowsSystem32 that has the right to automatically elevate privileges without displaying a UAC request (in this case, wusa.exe).

DLL hijacking is additionally used: a malicious library is placed in the fake directory under the name of one of the libraries imported by the legitimate file (in this case, wtsapi32.dll). As a result, when run from the fake directory, the legitimate file wusa.exe (or rather, the path to it) passes the authorization check due to the GetLongPathNameW API, which removes the space character from the path. At the same time, the legitimate file is run from the fake directory without a UAC request and loads a malicious library called wtsapi.dll.

Besides copying the legitimate system file to the fake directory and creating a malicious library there, the dropper creates another file named uninstall.pdg. After that, the malware creates and runs a series of BAT files that start wusa.exe from the fake directory and then clean up the traces by deleting the created directory and the easymule.exe dropper itself.

Development: enter Rovnix

The file uninstall.pdg clearly contains a packed executable file. It is designed to unpack the same malicious library that was previously downloaded using wusa.exe and DLL hijacking.

Uninstall.pdg

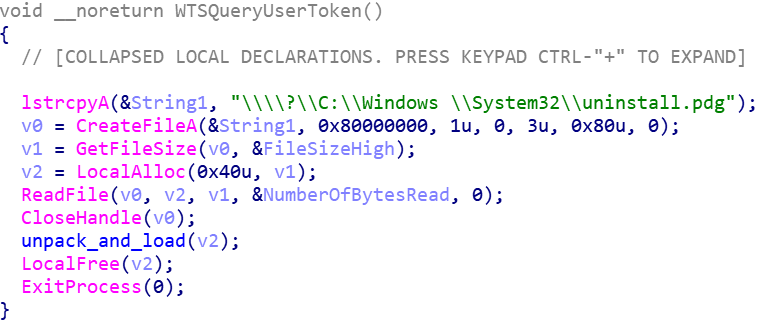

The code of the malicious library is kept minimal: the exported function WTSQueryUserToken obviously has no features required by the original wusa.exe, which imports it. Instead, the function reads uninstall.pdg, and unpacks and runs the executable from it.

Code of exported malicious library function

The unpacked uninstall.pdg turns out to be a DLL with the exported function BkInstall — another indicator that the malware is based on the leaked Rovnix code. Further analysis of the file confirms this.

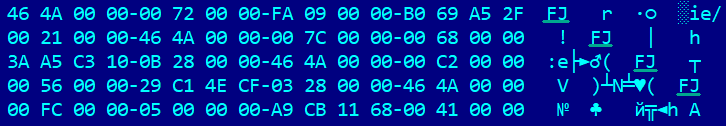

Glued inside uninstall.pdg are executable files packed with aPLib. The gluing was done using the FJ utility (also from the Rovnix bootkit), as evidenced by the file-unpacking algorithm and the FJ signatures indicating the location of the joint in the file.

FJ utility signature

The glued files are the KLoader driver from the leaked Rovnix bootkit and a bootloader. Uninstall.pdg unpacks them, overwrites the VBR with the bootloader, and places the packed original VBR next to it. In addition, KLoader is written to the disk; its purpose is to inject the payload into running processes.

Left: source code of the malware; right: leaked Rovnix source code (kloader.c)

As seen in the screenshot, the source code of the malware is not much different from the original. The original code was seemingly compiled for use without a VFS and a protocol stack for the driver to operate with the network.

In this instance, the driver injects a DLL into the processes, which is that same un-Rovnix-like loader that we spoke about at the very beginning.

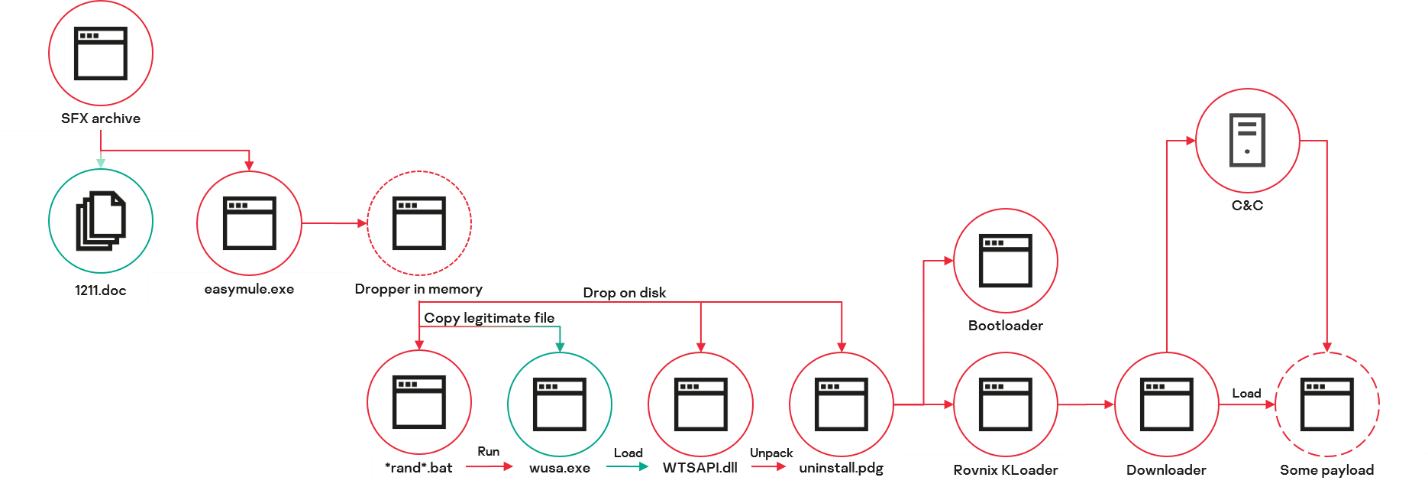

Thus, the general execution scheme looks as follows.

Execution scheme

Climax: enter loader

Let’s consider the new loader in more detail. The first thing to catch the eye is the PDB path in the file.

PDB path

When run, the malware first fills the structure with pointers to functions. The allocated memory is filled with pointers to functions, to be called subsequently by their offset in the allocated memory area.

Structure with functions

Next, the process obtains access to the Winsta0 and Default desktop objects for itself and all processes created by this process, and creates a thread with the C&C communication cycle.

Creating a C&C communication thread

Communication with C&C

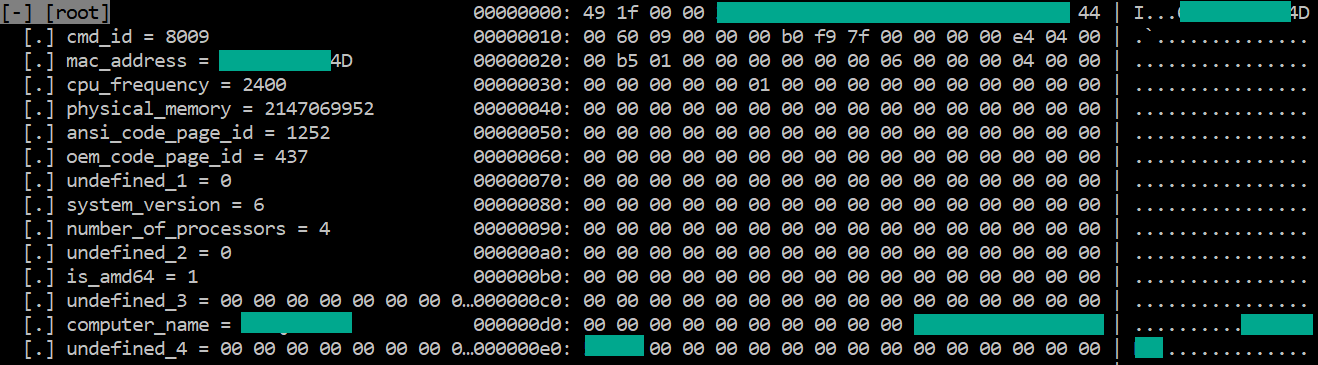

Having created the thread, the malware checks its presence in the system using OpenMutexA. It then starts a C&C communication cycle, within which a data packet about the infected device is generated. This packet is XOR-encrypted with the single-byte key 0xF7, and sent to C&C.

Structure of sent data

In response, the malware receives an executable file that is loaded into memory. Control is transferred to the entry point of this PE file.

Displaying the PE file loaded into memory

Denouement: enter testing

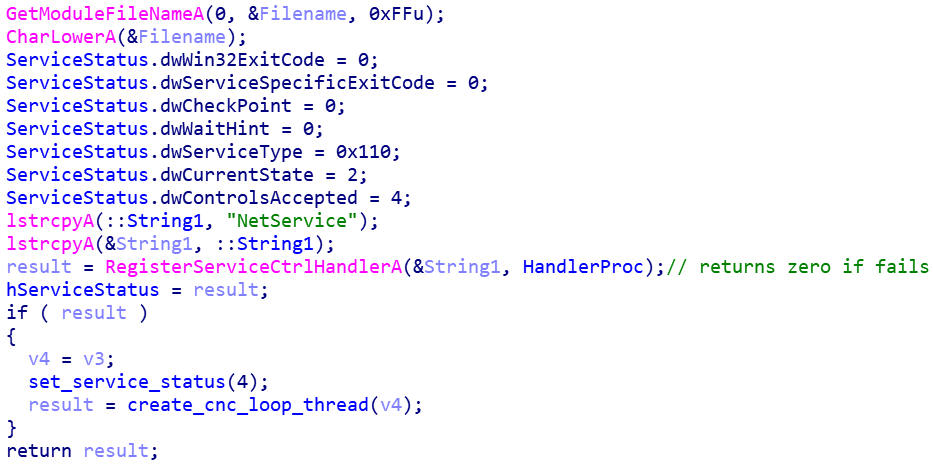

The loader turns out not to be unique: several more instances were discovered during the analysis. They all have similar features, but with slight differences. For example, one of them checks that it is running properly by trying to register a NetService handler. If it fails (that is, the service is not running in the system), the malware stops working.

Example of a different version of the loader

Other instances of the loader do not use the bootkit, but do apply the same UAC bypass method. All indications are that the loader is currently being actively tested and equipped with various tools to bypass protection.

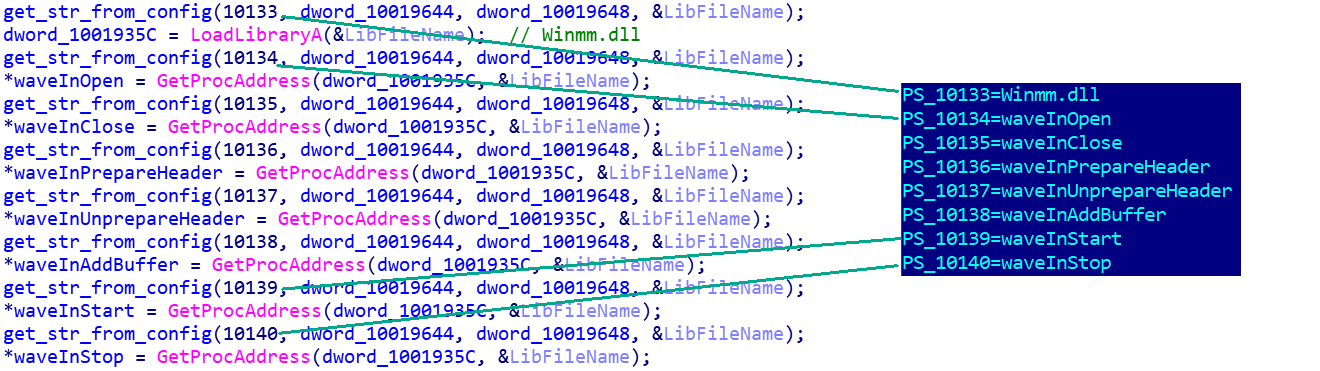

We also discovered instances that could serve as a payload for a loader. They contain similar PDB paths and the same C&Cs as the loaders. Interestingly, the addresses of the required APIs are got from the function name, which is obtained from the index in the configuration line.

Getting the API addresses

At the command of C&C, this malware can run an EXE file with the specified parameters, record sound from the microphone and send the audio file to the cybercriminals, turn off or restart the computer, and so on.

Processing a received command

The module name (E:LtdProductsProjectnewproject64bits64AllSolutionsReleasePcConnect.pdb) suggests that the developers are positioning it as a backdoor, which could additionally have Trojan-Spy elements, judging by some configuration lines.

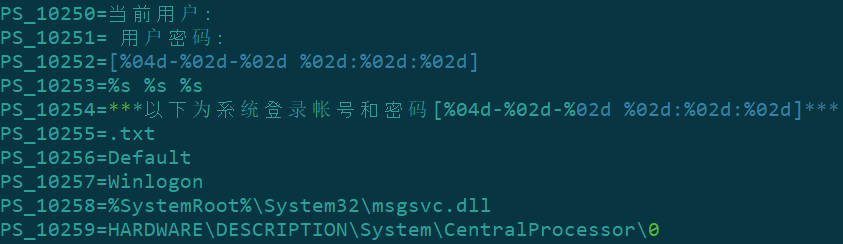

Configuration snippet; the lines in Chinese mean “Current user:”, “user password:”, “***Below are the system account and password [%04d-%02d-%02d %02d:%02d:%02d]***”

Epilogue

Our analysis of malware masquerading as a “new initiative of the World Bank” shows that even well-known threats like Rovnix can throw up a couple of surprises when their source code goes public. Freed from the need to develop their own protection-bypassing tools from scratch, cybercriminals can pay more attention to the capabilities of their own malware and add extra “goodies” to the source code, such as UAC bypass. Kaspersky products detect this threat and its related modules as Trojan.Win32.Cidox, Trojan.Win32.Generic, Trojan.Win32.Hesv, and Trojan.Win32.Inject.

IOC

7CFC801458D64EF92E210A41B97993B0

E2A88836459088A1D5293EF9CB4B31B7

bamo.ocry[.]com:8433

45.77.244[.]191:8090

45.77.244[.]191:9090

45.77.244[.]191:5050

45.76.145[.]22:8080

149.28.30[.]158:443

0 Commentaires